Indications

Lung ultrasound (LUS) is one of the most clinically useful scans for the Internist. Below are some of the indications for performing lung ultrasound:

- Undifferentiated dyspnea/respiratory failure/chest pain

- Known or suspected pleural effusion

- Suspected pulmonary edema

- Suspected pneumonia

- Suspected pneumothorax (advanced)

Acquisition

Either the curvilinear or phased array probe can be used for LUS. The curvilinear is favoured for novice users as it has a large footprint that allows for visualizing multiple ribs to help maintain orientation and depth to visualize small effusions. The linear probe is favoured for pleural pathology such as as pneumothorax, pleural irregularity, and sub-pleural consolidation. The phased array is also able to be used the same way as the curvilinear probe but is less favoured for novices as it can be easy to lose longitudinal orientation due to it fitting within the intercostal space.

There are several conventions to lung scanning, including 6, 8 and even 16 zone approaches. We favour the 8 zone approach outlined below. Feel free to watch this video from our partner YouTube channel POCUS in Practice or puruse the text description below.

How to Get the Views

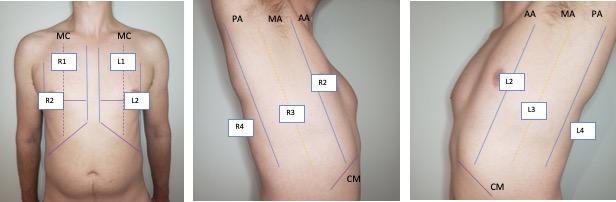

The chest is broken down into 8 zones with 4 zones per hemithorax. Zones R1-2 (R=right) and L1-2 (L = left) provide a survey of the anterior lung parenchyma while R3-4/L3-4 focus on detecting pleural/basal lung pathology.

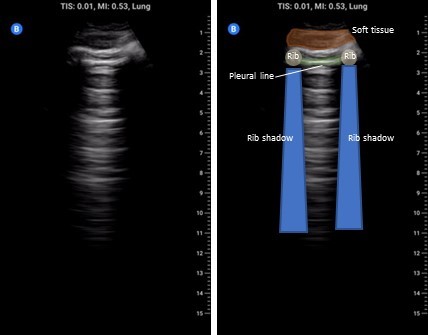

The cardinal anterior lung view (zones 1-2) is shown below and should include a single interspace with one rib on either side and be perpendicular to the pleura. Unless inspecting pleural pathology you should have the depth set to at least 10 cm below the pleural line to detect effusion, consolidation, and vertical artefacts (B-lines) from normal reverberation artefacts (Z-lines).

For the diaphragm/lung base views R3 and L3 the ideal view should include as much of the diaphragm as possible, the liver or spleen, and the vertebral column. You generally have to be quite posterior, usually the mid-axillary, and potentially even posterior-axillary to achieve these views. Remember, in a normal, well-aerated lung you should not be able to see anything below the pleural line and as lung enters the view everything below will be “greyed out”; this effect is known as “curtain sign”.

The R4/L4 zone is to assess for the so called PLAPS or posterolateral alverolarpleural syndrome. This zone is posterior to the posterior axillary line and is intended to assess for retrocardiac/paraspinal pneumonia/atelectasis frequently missed by chest x-ray. The normal anatomy is lung curtaining screen left and liver/spleen screen right.

Left: Cardinal R4 view showing lung, diaphragm, and liver. Right: Cardinal L4 view showing lung, diaphragm, and spleen.

Interpretation

Normal Findings

In this section we cover the typical sono-anatomy encountered during a comprehensive lung ultrasound. At present there remains much heterogeneity in how even normal findings are labelled and discussed with innumerable colloquial signs and terminology. We include the most common and generally used but expect these will continue to evolve over time.

Horizontal artefacts: Commonly known as A-lines these are a reverberation artefacts caused by the ultrasound beam reflecting between the pleural line and the transducer multiple times before being “sensed” by the probe resulting in regular parallel bright lines akin to ripples on a pond. These are generally a normal finding however if a strong A-line pattern is seen even in very dependent regions it supports the presence of hyperinflation states such as in COPD or gas trapping in asthma.

Z-lines: These are small vertical artefacts that arise from the pleural interface and are mostly seen only when using the linear transducer. The mechanism and significance of Z-lines is uncertain other than they are not pathologic. They are most likely small reverberation artefacts that originate from the pleural line and project down but only shallowly i.e. less than 10 cm. They can be helpful when excluding pneumothorax as their presence means that the visceral and parietal pleura are in contact.

Lung sliding: As part of a standard approach to lung ultrasound you should look for and report lung sliding in every view. To properly visualize, use a low depth setting or switch to the linear probe and look at the pleural line; it should appear bright and have a shimmering appearance as the visceral pleura slides along the parietal pleural. It may also appear somewhat beaded and sliding appears to look like “ants marching across a log”. The absence of lung sliding can be indicative of pneumothorax and requires more investigation.

Lung pulse: You may not always see the pleura sliding in accordance with the respiratory cycle, especially near the apex or in individuals with hyperinflation. However you may see that lung pulse, from the mechanical force of cardiac systole being propagated through lung tissue. This is an important finding for ruling OUT pneumothorax as the presence of lung pulse means the pleural interface must be intact.

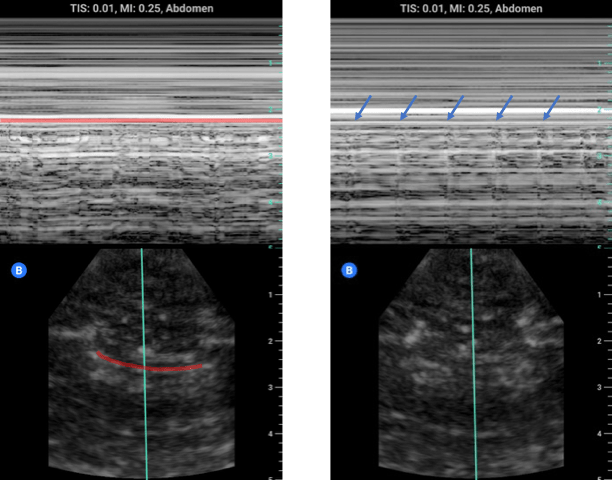

M-Mode and Pleural Sliding: In addition to B-mode imaging, M-mode can be used to assess for the presence of pleural sliding and lung pulse. In the image above on the left we see M-mode being used on a shallow lung view with the pleural line highlighted in red. Note the static soft-tissue/intercostal muscles above the line create layers of horizontal lines whereas BELOW the pleural line there is a scattered random pixel pattern. This is due to the motion of the intact pleural interface and the scatter from the lung parenchyma colloquially referred to as “sea shore” sign where the lung is the sand and the soft tissue the water. Even if the lung is not moving there should still be movement of the pleura from the heart/aorta creating a lung pulse which can be seen below the blue arrows.

Pleural line: In each view inspect the pleural line using a low depth setting. Normally the pleura is hyperechoic with a smooth contour. If it appears irregular always fan back and forth and see if you can make it more regular appearing as even normal pleura can look irregular when not imaged at 90 degrees. A thick ragged pleural line can indicate an inflammatory/fibrotic process.

Pathologic Findings

There are a significant number of pathologies encountered in lung ultrasound. This is not an exhaustive list as chest wall abnormalities, tumours, diaphragm dysfunction, and even aortic pathology can be encountered during lung scanning. These are among the more common findings BUT remember if you don’t know what you are looking at, find a colleague who may, and short of that pursue comprehensive imaging.

Vertical Artefacts (B-lines): More commonly known as B-lines these are also reverberation artefacts; their origin is controversial but there is evidence to suggest that they are from thickening of the interlobular septae (lung interstitium) causing acoustic traps. This thickening can be due to fluid, blood, inflammation, or fibrosis. In terms of appearance, they arise from the pleural line and project down greater than 10 cm of depth. Three or more B-lines in a single interspace is considered pathologic and should prompt a search for the presence of pathology in other lung zones. The presence of pathologic B-lines in 2 or more rib space bilaterally constitutes a diffuse interstitial syndrome. The differential for focal versus diffuse B-lines is discussed below

Focal: Lobar pneumonia, lung infarct from pulmonary embolism, lobar atelectasis, lung injury (trauma, radiation, prior infection), neoplasm, amniotic fluid embolism

Bilateral: Cardiogenic pulmonary edema, ARDS, interstitial lung disease, organizing pneumonia, bilateral bacterial pneumonia, viral pneumonias (influenza, COVID-19, RSV, etc.)

Pleural effusion: The presence of anechoic material above the diaphragm is indicative of pleural fluid. To call an effusion definitively you must be able to show the spine below the fluid on the screen. This is called “spine sign”. The presence of dark material above the diaphragm but without being able to see the spine may be an artefact. We discuss this in our ‘Pitfalls’ section.

Complex effusion: Pleural fluid that is simple is generally uniformly anechoic and collects in the most gravity dependent location. The presence of septations or debris (e.g. “plankton sign”) can indicate a complicated effusion and raises the possibility of empyema. Simple pleural fluid appearance on ultrasound DOES NOT exclude empyema. The image on the left shows a mature empyema with heavy septations.

Consolidation: This is a broad term applied to the finding of echogenic lung parenchyma. Recall that normally lung tissue cannot be imaged by ultrasound due to the presence of air in the lung parenchyma. With consolidation the lung has a similar appearance to the liver; for this reason this is sometimes called ‘hepatization’ of the lung. Consolidation is most often seen with atelectasis especially in the context of effusion, but is also seen with pneumonia or any disease process that causes dense airspace disease and can be as small as a few millimetres below the pleural line (sub pleural consolidation – image above on the left) to an entire lobe (translobar – image above on the right) The clip on the right shows very dense disease from pneumonia and has a small pleural effusion as well e.g. a translobar process. The bright white areas areas in the consolidated lung are called ‘air bronchograms’; these arise from air in small airways with surrounding consolidation and is essentially the same process that leads to air bronchograms on chest x-ray.

Dynamic air bronchograms: Air bronchograms are of two varieties static and dynamic. The image above shows static air bronchograms which are punctate or linear hyperechoic regions within consolidated lung. Dynamic air bronchograms as their name suggests move. They are thought to represent ‘bubbles’ of air with debris on either side and move with respiration. There is some evidence to suggest this may be a more specific sign for pneumonia versus atelectasis. This is a very striking example of this phenomena.

Pleural disease: Normally the pleura should be thin, smooth, and hyperechoic. An irregular “ragged” pleural line can indicate underlying inflammatory state (e.g. pneumonia), pleural mets/malignancy, ILD, or even chronic remodelling with advanced heart failure. In this example there are B lines here but focus on the pleural line; it is ragged and irregular, this patient actually has amyloidosis with lung/pleural involvement.

Absent lung sliding: A loss of lung sliding is a potential pathologic findings that may indicate pneumothorax. This may also occur with lung hyperinflation (COPD/asthma), bullous lung disease, an acute mucus plug, lung pleurodesis, or on the contralateral side of mainstem bronchus intubation Detecting a loss of lung sliding is an advanced skill and therefore outside of patients with hemodynamic collapse we ALWAYS recommend chest x-ray if pneumothorax is suspected. Practically, there are almost no scenarios where a clinically significant pneumothorax will not appear on x-ray especially if assessed serially.

Barcode sign: This is an advance maneuver for further increasing probability of a pneumothorax. Using M-mode on the same clip as above we see only layers of continuous line with no “noise” or random pixel pattern below the hyperechoic pleural line near the top quarter of the screen. It is quite challenging to maintain sufficient steadiness of the hand to produce this effect therefore while we include this finding for completeness it is not recommended.

Lung Point: A lung point is the only absolute diagnostic finding of a pnuemothorax. It is when the clinician encounters the precise point where the edge of the pneumothorax ends and lung that is still in contact with the parietal pleura begins shown in the image on the left. It is not necessary to find a lung point when pneumothorax and as stated previously ultrasound should almost never be the final imaging modality before determining intervention.

Pearls

B-line distribution: B-lines can be seen with a myriad of different pathology however the distribution of B-lines themselves can provide a clue to their origin. B-lines that are worse in dependent regions and less pronounced in more apical lung zones are more suggestive of pulmonary edema. Conversely random clustering that does not respect gravity is more likely with inflammatory (ARDS, interstitial pneumonia) or fibrotic processes.

Excluding rib shadow: Especially in the R3/L3 zones rib shadow can be a challenge to viewing critical structures and pathology. Though lung ultrasound is largely done in the longitudinal orientation it is acceptable to use a slight oblique angle to align with the curved rib space. In R3 rotate the probe around 10-20 degrees counterclockwise from true cranial-caudal orientation; the maneuver is reversed in L3 rotating 10-20 degrees clockwise.

Pitfalls

Not all B-lines are pulmonary edema: Remember B-lines are a non-specific finding and have a wide differential, just because you see B-lines doesn’t mean you start giving furosemide. As above look for the company B-lines keep; if a patient has B-lines that are bilateral, worse in dependent areas, and with a regular pleura then this increases the likelihood they represent pulmonary edema. However if they are randomly dispersed, unilateral, or have pleural abnormalities it suggests alternate causes.

Mirror artefact and the diaphragm: Look at the image below on the left, is there a pleural effusion above the liver? No! Then what is that dark grey above the diaphragm? What we are seeing is a mirror artefact. The ultrasound beam reflects off of the diaphragm strikes the liver parenchyma then returns to the transducer. Due to the increased time the echo took to return the computer interprets this and renders an image showing liver parenchyma below the diaphragm; its an error but can look like an effusion. To distinguish between mirror-artefact and effusion look for the spine! An effusion creates a window to the spine that would ordinarily be sacred by lung tissue. If you see anechoic material and spine below you have an effusion. If you don’t see the spine you cannot rule in an effusion.

Physiologic lung point: While use of minimal depth or the linear probe does allow excellent visualization of the pleura it is not without problems. In this clip, at first blush, you might think you have stumbled across a lung point. However on closer inspection you note the regular pulsations and what looks like tissue. This is what is termed a physiologic lung point, or the interface between the lung and an organ outside the pleural space in this case the heart. The correction is to increase the depth which will allow you to resolve whether this is another organ versus the border of a pneumothorax.