Indications

Lung ultrasound is one of the most clinically useful scans for the Internist. Below are some of the indications for performing lung ultrasound:

- Undifferentiated dyspnea/respiratory failure

- Known or suspected pleural effusion

- Suspected pulmonary edema

- Suspected pneumonia

- Suspected pneumothorax (advanced)

Acquisition

Typically the curvilinear probe is favoured as it has a large footprint that allows for visualizing multiple ribs to help maintain orientation and depth to visualize small effusions. The linear probe is favoured for pleural pathology such as as pneumothorax, pleural irregularity, and sub-pleural consolidation. The phased array is also able to be used the same way as the curvilinear probe but is less favoured for novices as it can be easy to lose longitudinal orientation due to it fitting within the intercostal space.

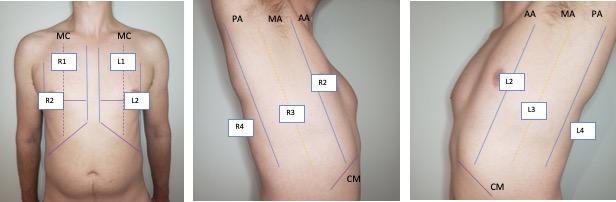

There are several conventions to lung scanning, including 6, 8 and even 16 zone approaches. We favour the 8 zone approach outlined below. Zones R1-2 (R=right) and L1-2 (L = left) provide a survey of the pleura. R3-4/L3-4 is to detect pleural effusions/basal lung pathology.

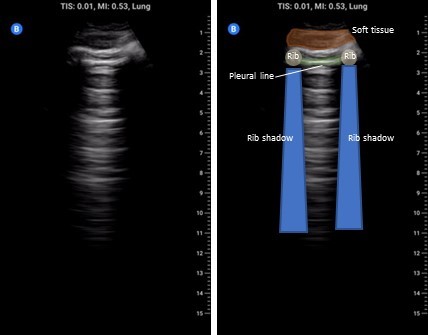

The cardinal anterior lung view (zones 1-2) is shown below and should include a single interspace with one rib on either side and be perpendicular to the pleura. Unless inspecting pleural pathology you should have the depth set to at least 15 cm to detect effusion, consolidation, and 10 cm to distinguish B-lines from Z-lines.

For the diaphragm/lung base views R3 and L3 the ideal view should include as much of the diaphragm as possible, the liver or spleen, and the vertebral column. You generally have to be quite posterior usually the mid-axillary and potentially even posterior-axillary to achieve these views. Remember in normal well aerated lung you should not be able to see anything below the pleural line and as lung enters the view everything below will be “greyed out”; this effect is known as “curtain sign”.

The R4/L4 zone is to assess for the so called PLAPS or posterolateral alverolarpleural syndrome. This zone is posterior to the posterior axillary line and is intended to assess for posterior pneumonia/atelectasis frequently missed by chest x-ray. The normal anatomy is lung curtaining screen right and liver/spleen screen right.

Left: Cardinal R4 view showing lung, diaphragm, and liver. Right: Cardinal L4 view showing lung, diaphragm, and spleen.

Interpretation

Normal Findings

A-lines: These are a reverberation artefact caused by the ultrasound beam bouncing between the highly reflective pleural line and the transducer resulting in regular parallel bright lines. These are generally a normal finding however if a strong A-line pattern is seen even in very dependent regions it supports the presence of hyperinflation states such as in COPD.

Z-lines: The mechanism and significance of Z-lines is uncertain other than they are not pathologic. They are most likely small reverberation artefacts that originate from the pleural line and project down but only shallowly i.e. less than 10 cm. They can be helpful when excluding pneumothorax as their presence means that the visceral and parietal pleura are in contact.

Lung sliding: As part of a standard approach to lung ultrasound you should look for and report lung sliding in every view. To properly visualize, use a low depth setting or switch to the linear probe and look at the pleural line; it should appear bright and have a shimmering appearance as the visceral pleura slides along the parietal pleural. It may also appear somewhat beaded and sliding appears to look like “ants marching across a log”. The absence of lung sliding can be indicative of pneumothorax and requires more investigation.

Pleural line: In each view inspect the pleural line using a low depth setting. Normally the pleura is hyperechoic with a smooth contour. If it appears irregular always fan back and forth and see if you can make it more regular appearing as even normal pleura can look irregular when not imaged at 90 degrees. A thick ragged pleural line can indicate an inflammatory/fibrotic process.

Pathologic Findings

B-lines: These are also reverberation artefacts; their origin is controversial but there is evidence to suggest that they are from thickening of the interlobular septae (lung interstitium). This thickening can be due to fluid, blood, inflammation, or protein. In terms of appearance, they arise from the pleural line and project down greater than 15 cm of depth. A single B-line is not significant but 3 or more in a single interspace is considered pathologic and should prompt a search for the presence of pathology in other lung zones. The presence of pathologic B-lines in more than one rib space bilaterally constitutes a pulmonary interstitial syndrome. The differential for unilateral and bilateral B-lines is discussed below

Unilateral: Lobar pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, lobar atelectasis, neoplasm, amniotic fluid embolism

Bilateral: Pulmonary edema, ARDS, interstitial, pneumonia, COVID-19, ILD

Pleural effusion: The presence of anechoic material above the diaphragm is indicative of pleural fluid. To call an effusion definitively you must be able to show the spine below the fluid on the screen. This is called “spine sign”. The presence of dark material above the diaphragm but without being able to see the spine may be an artefact. We discuss this in our ‘Pitfalls’ section.

Complex effusion: Pleural fluid that is simple is generally uniformly anechoic and collects in the most gravity dependent location. The presence of septations or debris (e.g. “plankton sign”) can indicate a complicated effusion and raises the possibility of empyema. Simple pleural fluid appearance on ultrasound DOES NOT exclude empyema. The image on the left shows a mature empyema with heavy septations.

Consolidation: This is a broad term applied to the finding of echogenic lung parenchyma. Recall that normally lung tissue cannot be imaged by ultrasound due to the presence of air in the lung parenchyma. With consolidation the lung has a similar appearance to the liver; for this reason this is sometimes called ‘hepatization’ of the lung. Consolidation is most often seen with atelectasis especially in the context of effusion, but is also seen with pneumonia or any disease process that causes dense airspace disease and can be as small as a few millimetres below the pleural line (subpleural consolidation) to an entire lobe (translobar) The clip on the left shows very dense disease from pneumonia and has a small pleural effusion as well e.g. a translobar process. The bright white areas areas in the consolidated lung are called ‘air bronchograms’; these arise from air in small airways with surrounding consolidation and is essentially the same process that leads to air bronchograms on chest x-ray.

Dynamic air bronchograms: Air bronchograms are of two varieties static and dynamic. The image above shows static air bronchograms which are punctate or linear hyperechoic regions within consolidated lung. Dynamic air bronchograms as their name suggests move. They are thought to represent ‘bubbles’ of air with debris on either side and move with respiration. There is some evidence to suggest this may be a more specific sign for pneumonia versus atelectasis. This is a very striking example of this phenomena.

Pleural disease: Normally the pleura should be thin, smooth, and hyperechoic. An irregular “ragged” pleural line can indicate underlying inflammatory state (e.g. pneumonia), pleural mets/malignancy, ILD, or even chronic remodelling with advanced heart failure. In this example there are B lines here but focus on the pleural line; it is ragged and irregular, this patient actually has amyloidosis with lung/pleural involvement.

Absent lung sliding: A loss of lung sliding is a potential pathologic findings that may indicate pneumothorax. This may also occur on the contralateral side of mainstem bronchus intubation, or with bullous disease. Supporting signs of pneumothorax are absence of B or Z-lines, “bar-code” sign on M-mode, absent lung pulse, or the presence of a lung point (or where the lung visceral pleura loses contact with the parietal pleural where the pneumothorax begins). We consider this an advanced application and recommend always getting at least a chest x-ray if pneumothorax is suspected.

Pearls

B-line distribution: B-lines can be seen with a myriad of different pathology however the distribution of B-lines themselves can provide a clue to their origin. B-lines that are worse in dependent regions and less in more apical lung zones are more suggestive of pulmonary edema. Conversely random clustering that does not respect gravity is more likely with inflammatory (ARDS, interstitial pneumonia) or fibrotic processes.

B lines vs Z-lines: It can be easy to confuse Z-lines with B-lines but there are some important characteristics that can help to differentiate. Z-lines never extend further down than a few centimetres from the pleural line before fading out; by contrast B-lines project down greater than 15 cm. Z-lines also tend to be quite diminutive only being a few millimetres wide and are often isolated whereas B-lines can take up an entire interspace; these are also called confluent B-lines.

Lung pulse: This refers to the pleural movement caused by the beating of the heart. This can be helpful in determining whether a pneumothorax in patients with hyperinflation or who are intubated where lung sliding may be diminished. If a lung pulse is present this excludes pneumothorax at that interspace.

Pitfalls

Not all B-lines are pulmonary edema: Remember B-lines are a non-specific finding and have a wide differential, just because you see B-lines doesn’t mean you start giving furosemide. As above look for the company B-lines keep; if a patient has B-lines that are bilateral, worse in dependent areas, and with a regular pleura then this increases the likelihood they represent pulmonary edema. However if they are randomly dispersed, unilateral, or have pleural abnormalities it suggests alternate causes.

Mirror artefact and the diaphragm: Look at the image below on the left, is there a pleural effusion above the liver? No! Then what is that dark grey above the diaphragm? What we are seeing is a mirror artefact. The ultrasound beam reflects off of the diaphragm strikes the liver parenchyma then returns to the transducer. Due to the increased time the echo took to return the computer interprets this and renders an image showing liver parenchyma below the diaphragm; its an error but can look like an effusion. To distinguish between mirror-artefact and effusion look for the spine! An effusion creates a window to the spine that would ordinarily be sacred by lung tissue. If you see anechoic material and spine below you have an effusion. If you don’t see the spine you cannot rule in an effusion.