Indications

Assessment of the right ventricle (RV) function is a useful application in terms of hemodynamic management of sick patients as well as the identification of hyperacute life threatening illnesses but is technically challenging to perform and nuanced in interpretation. Its main indications are below:

- Undifferentiated hypotension/shock

- Undifferentiated chest pain/dyspnea

- Volume status assessment

- Suspected pulmonary embolism

Acquisition/Interpretation

There are two main aspects of RV assessment: size and function as both RV enlargement and impaired function can be heralding signs of either acute or chronic pulmonary hypertension which may have significant consequences to hemodynamics and cardiac output. Both require parasternal long axis (PLAX), short axis (PSAX), and apical four chamber views (A4C).

In each view we will assess specific qualitative aspects of how to assess for RV size/function.

PLAX

In the PLAX we really are only looking for the suggestion of RV dilation as little else can be gleaned given all we see is the RVOT in this view. The 2D measurement of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) diameter from this view involves measurement of the lumen from the anterior wall of the RVOT to the septum at the level of the aortic valve during end diastole but this has been simplified into an approximation using the so called “rule of 1/3’s” where the relative diameter of the RVOT, aortic root, and left atria should be approximately the same. Therefore an increased ratio in favour of the RVOT suggests RV dilation as is shown in the clip on the right below.

PSAX

In the PSAX at the mid papillary level dilation can be assessed but our recommendation is to avoid this given the ability to over or underestimate the RV size. It is more important to note the potential hemodynamic effect of an enlarged/failing RV which is demonstrated with a high degree of clarity through the septal kinetics of the RV and LV in this view. If there is significant pressure or volume overload on the part of the RV the LV will be distorted developing a ‘D shaped’ appearance. Flattening during systole is consistent with high RV afterload or pressure overload while flattening during primarily diastole is consistent with volume overload. Flattening throughout the cardiac cycle most often reflects progression of pressure overload to include volume overload from progressive RV failure.

A4C

RV Size

In terms of RV size, the A4C is the ideal view for visual estimation. The primary approach is to compare to the LV. Usually the RV is 2/3 the area of the LV. In moderate dilation the RV is roughly equal to the LV and when it is severely dilated will be larger. In the image on the left the RV is of normal size and on the right is severely dilated. Another visual clue regardingRV enlargement is which ventricle “owns” the apex. Normally the LV is the true apex of the heart but in the setting of severe RV dilation the RV will predominate.

Though the circumstances where direct measurement in POCUS are limited it is still worth knowing the cutoffs for RV enlargement. The location and measures consistent with RV enlargement for the annulus, mid cavity, and basal to apical length are shown below.

RV Function

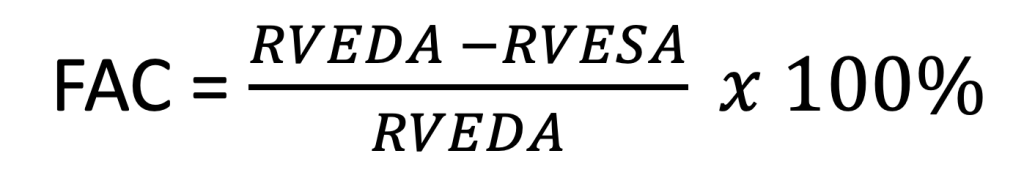

From a function perspective, in the A4C we observe for if the longitudinal motion of the RV free wall toward the apex is preserved and if the area decreases during systole. The former is based on the M-mode measurement known as TAPSE or tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and the latter the concept of fractional area change (FAC).

Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion

Measuring TAPSE involves aligning an M-mode line with tricuspid annulus in the A4C and measuring the longitudinal movement of the annulus toward the apex from end diastole (the valley) to peak systole (the peak). TAPSE <17 mm is consistent with impaired RV function.

Practically, we support a qualitative approach where the question is geared toward identifying severe impairment; i.e. does the tricuspid annulus seem to move vigorously and around 2 cm by the depth markers toward the apex (image on the left below) or is there minimal longitudinal translation (as shown in the image on the right).

TAPSE can be estimated from the subcostal view using a similar approach but it is less common to see it used quantitatively as the alignment rarely allows for an accurate M-mode reading given the contraction moves across the screen as opposed to vertically. Normal visual TAPSE is shown on the left; impaired on the right.

Fractional Area Change

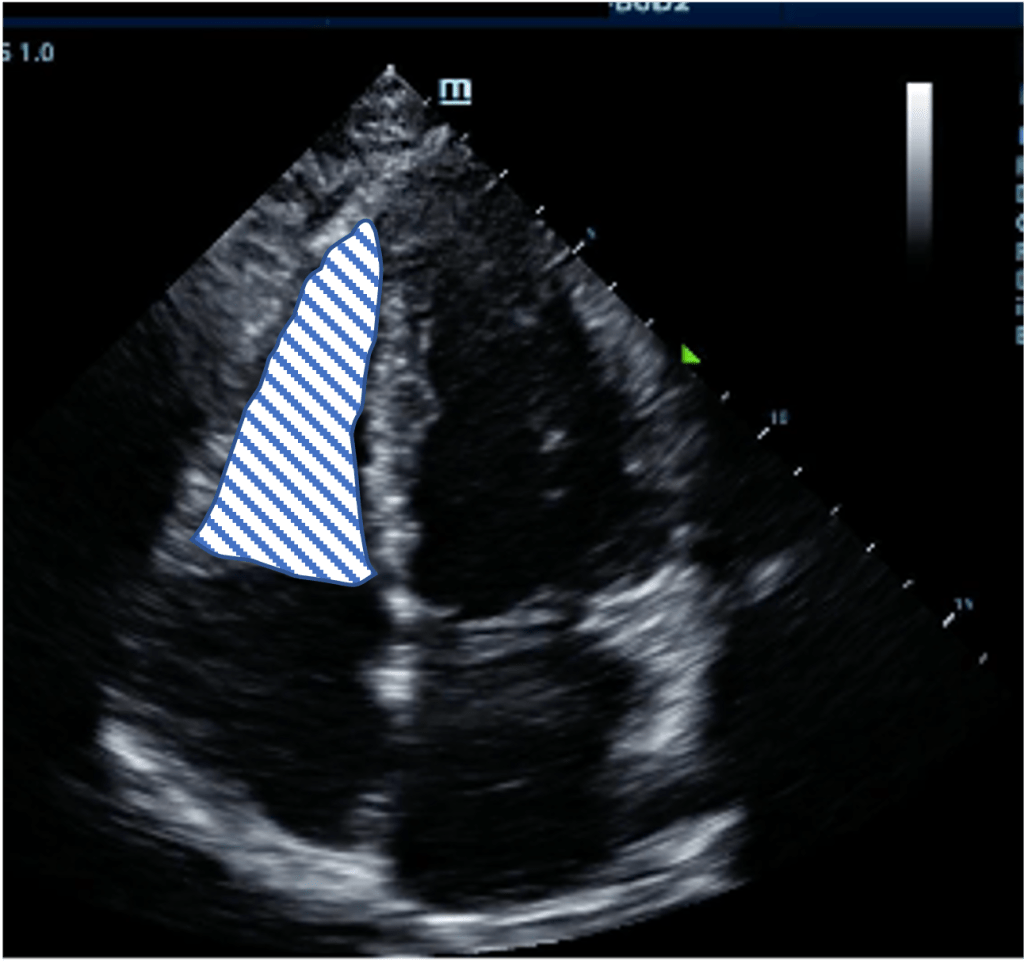

Though not performed in the context of POCUS given its time consuming nature we borrow from the concept of fractional area change (FAC) for RV function estimation. FAC requires tracing the border of the RV endocardium excluding trabeculae during end diastole (left image below) and end systole (right) and calculatin the delta as a percentage of end diastolic area. FAC of <35% is consistent with impaired RV function. We use the principle of this to judge whether the area changes substantially or minimally over the cardiac cycle.

RV Free-Wall Motion

Though not based on any objective 2D measurement, a lack of movement of the free wall from the A4C is important as it is a marker of RV infarction in large volume pulmonary embolism. This is the setting where the McConnell’s sign may be seen; where due to RV free wall akinesis and a stressed hyperdynamic left ventricle creates the illusion of a hyperdynamic RV apex. It is insensitive but specific for large volume acute pulmonary embolus.

Pitfalls

For all size assessment since we are using an “eyeball” approach without direct measurement we are dependent on relative comparison to other cardiac chambers which assumes they are normal. The rule of 1/3’s in the PLAX becomes much more challenging in the setting of concurrent left atrial dilation, aortic root dilation, or both! Similarly comparison to the LV from the A4C assumes the LV is of normal size therefore be very wary with decline in LVEF and consider actually measuring if it would change your management in some way.

TAPSE whether measured by eyeball or M-mode can both over and underestimate RV function. The greater risk is underestimation which usually occurs from measuring from too close to the septum away from the RV free-wall where longitudinal contraction is not the predominant plane. Overestimation can occur in the setting of hyperacute RV failure such as massive PE where a hyperdynamic left ventricle can exaggerate RV movement. For example visually the RV below may not look awful in terms of the visual TAPSE but with massive dilation, an akinetic free wall, this is largely the work of the LV that is working hard against these conditions to maintain cardiac output.

An area that is quite frought with error is the approach, in particular during a cardiac arrest, is to judge whether the RV is dilated as a sign of acute PE. Putting aside the fact that RV frequently becomes dilated during cardiac arrest regardless of the presence of embolus the subcostal view frequently underestimated RV signs as it is generally quite an inferior angle which tends to “shrink” the RV. The views below of the subcostal (left) and A4C (right) are from the same patient which while the RV appears impaired by visual TAPSE in the subcostal views and perhaps moderately enlarged as it is close in size to the LV we see this is a gross underestimate when viewing from the A4C an RV that is dwarfing it neighbour.

Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is extremely common among the general population (~80% prevalence). It is relevant in RV dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension as it acts as a pressure release valve for a struggling RV. If there is substantial TR it may be cause to suspect RV function is overall worse than what is visually represented via TAPSE/FAC. In the image on the left (below) this is a severely dilated poorly functioning RV, but it is probably still even worse than what we can appreciate with annular dilation driving a large amount of TR that effectively offloads the RV to some degree. Why we care is it reflects a very tenuous state from a hemodynamic standpoint as patients with poor RV function and high RV afterload risk circulatory collapse with further increases in RV afterload, bradycardia, atrial arrhythmias, and negative inotropy of all causes (acidosis, medications, etc) and though they will often need decongestion/volume removal they are prone to hypotension with sudden shifts in intravascular volume.